The government’s most recent policy decision to jolt the economy back to life is to provide a sharp cut in taxes to India’s corporate sector. This new ‘reform,’ described by the industry lobbying group ASSOCHAM as “historic” and a “game changer,” will see corporate taxes drop from 30 per cent to 22 per cent, a touch below the global average of 23.79 per cent.

The rationale behind tax cuts is pretty straightforward: lowering tax rates will incentivise corporations to invest, which will create new jobs and hence boost demand, bringing the economy back on track. The argument seems convincing, even uncontroversial — almost common sense. But like other dogmas of the Church of Neoliberalism, this line of reasoning too withers away with the slightest bit of scrutiny.

To begin with, corporations do not invest simply because there is an abstract ‘incentive’ to do so. They invest only if they are assured of a return on their investment, barring which not even the grandest sops can induce them to part with their money (they would rather make a quick and healthy return on their capital by engaging in financial speculation). The avenues that promise returns on private investment are exports and domestic consumption, and it is to these that we turn our attention to now.

Weak exports

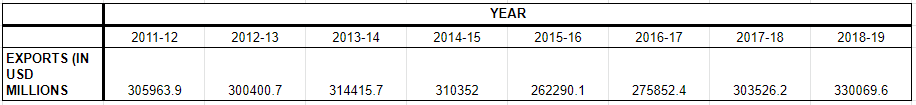

India’s export growth over the last eight years has been anything but spectacular, as revealed by data from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

In fact, in value terms exports have been contracting after reaching a high of more than USD 314 billion in 2013-14, predicted to be exceeded in 2018-19 (based on provisional figures), although it would require a hefty 8.74 per cent growth over the previous year’s exports. This, however, is quite unlikely, as global macroeconomic conditions do not appear to be conducive for such growth. As economists Jayati Ghosh and CP Chandrashekhar have noted, weak demand from developed countries can only partially explain the fall in exports of developing countries like India, as exports to other developing countries have registered a much sharper decline.

“Much of this decline [value of exports] was due to South-South trade [between developing countries],” they write. “While exports to the advanced economies declined by 20 per cent over this three-year period, those to developing countries fell by 25 per cent.” A significant factor in the fall of South-South trade has been China’s evolving economic strategy. “One of the most widely remarked features of recent world trade has been the dramatic emergence of China as a substantial player in global trade,” Ghosh and Chandrashekhar point out, “not only because its exports have penetrated nearly all countries’ markets, but because it had become a major destination for developing country exports, for both raw material and intermediate exports in particular.” But the US-China trade war, among other reasons, has shifted China’s focus “towards more domestic demand-led growth rather than export-led growth,” which “requires less imports from developing countries to use in processing for further export”. They conclude that “China is unlikely to play the same role of providing a much-needed demand impetus for developing country exports, that it played in the earlier decade”.

Under such adverse conditions, a tax cut-powered export boom, and subsequent economic recovery, seems like a remote possibility in India.

Muted domestic consumption

Much has already been said about the grim condition of domestic demand in the country. In a previous article, we have also shown this to be largely the result of near-stagnating incomes of the bottom 90 per cent of India’s working population. Corporate tax cuts may stimulate demand slightly if the benefits are passed on to the consumers. But this, too, seems improbable given that prices have already been slashed to counter the slowdown and in anticipation of the festive season.

It is more likely, thus, that the corporate sector will utilise the funds saved from taxes to either deleverage (pay back debts), reward investors with higher dividends or buy back shares to boost their stock price. Even if there is a slight uptick in demand, Indian corporations are more likely to increase capacity utilisation (which has hovered in the early to mid 70 per cent region for the last six years), rather than invest in new projects. In fact, new investment proposals in 2018-19 have been the lowest since 2004-05, with both public and private sectors’ contributions coming down. Thus, a domestic consumption-led recovery, too, seems improbable in the current climate.

Government intervention

Government spending which puts more money in the pockets of people (by providing employment and higher wages) or helps people save more (through subsidies and welfare policies), can stimulate demand. But the Church of Neoliberalism deems all government intervention meant to benefit the public heresy, and demands that they be placed at the mercy of market forces. To ensure that this dogma is not subverted, the government has made such a mess of public finances that it cannot intervene substantially, even if it wished to do so.

For starters, the government claimed to have gathered Rs 1.65 lakh crore more in tax revenues in 2018-19 than it actually did. This shortfall came to the fore because of a discrepancy in the tax revenue figures in the Economic Survey and the Budget documents; the former provides ‘Provisional Actuals,’ a more reliable and accurate estimate of government finances than the ‘Revised Estimates’ provided in the latter. This revenue shortfall, caused no doubt by less than estimated GST collections, caused the government to decrease expenditure, which it had overstated by Rs 1.45 lakh crore in the Budget. With the economy in a much poorer shape than it was last year and the government’s finances already strained, one can expect a greater cut to public expenditure as revenue targets for the current year are nearly impossible to attain.

The tax cuts, however, compound this dismal picture as they will cost the government another Rs 1.45 lakh crore. Wedded as we are to the idea of strict fiscal discipline (another dogma), the government has signaled it will pursue privatisation of public resources in order to make up for the revenue shortfall.

The perverse, circular logic of neoliberalism is on full display here: strap public finances so the government cannot intervene to boost demand; provide tax cuts to corporations which, in the absence of demand, will use them to line their pockets, while also straining public finances; and finally, try to make up for the revenue foregone by auctioning off public resources. Seen in this light, tax cuts appear to be blatant cash-grab, rather than a sound policy for economic rejuvenation.