The global economy today resembles the Titanic in the moments following the iceberg impact — doomed to sink, it will drag the poor with it into the icy abyss of a recession, while the rich will escape largely unscathed. Unlike the Titanic, though, those at the helm the moment the crisis hits will not have the decency to go down with it.

In India, the auto industry is in tatters, real estate is in a slump, manufacturing is slowing down, fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) are not moving fast enough, textiles and tea industries are pleading for government help, and the agrarian sector has been facing distress for five years now. Unemployment, already at an historic high, can only be expected to surge drastically from this point on, and that will only exacerbate the severity of the slowdown.

As has been abundantly clear, the roots of the slowdown lie in a general deficiency of demand. This diagnosis runs counter to everything we have heard over the last few decades about the growth of the Indian economy from the government, liberal intellectuals and the media, who have insisted that neoliberal capitalism is the only development paradigm that can work. That claim can now be justifiably questioned, because, it is becoming increasingly obvious that the so-called ‘fastest growing major economy’ in the world has failed to put money in the pockets of the vast majority of the people.

Looking for answers

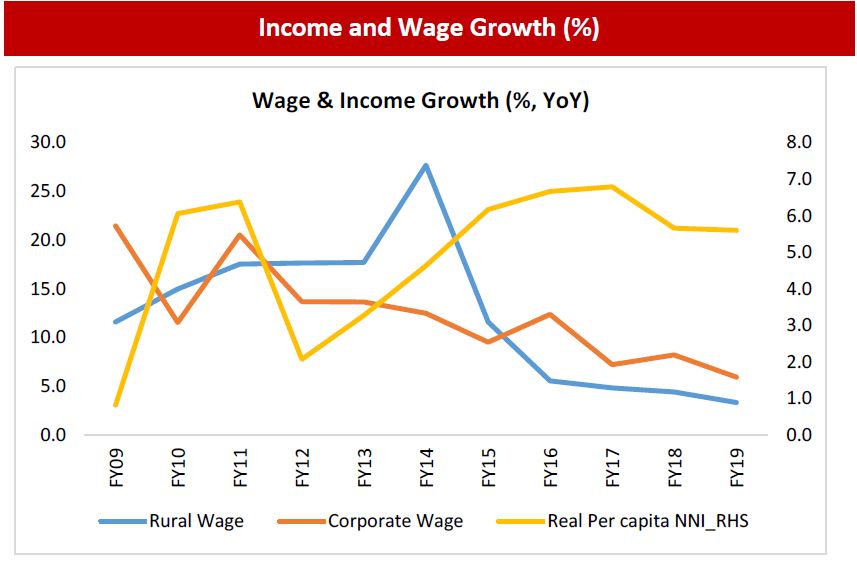

Writing in the Indian Express, Soumya Kanti Ghosh, chief economic advisor at the State Bank of India (SBI), confirmed this thesis by tying the current crisis to stagnating wages (Reading the slowdown, August 14). According to Ghosh, “the most crucial factor that is reinforcing the demand slowdown is slow growth of both corporate (a proxy for urban wages) and rural wages”. After peaking at 21.4 per cent in FY09, corporate wage growth has been on a downward trend and is now down to single digits, Ghosh writes. He further points out that rural wages, which grew at 27.7 per cent in FY14, have been registering growth of less than 5 per cent in the last three years. The conclusion drawn from these figures is that “decline in wage growth and structural changes have resulted in stagnating per capita income growth (in real terms) and hence to keep the consumption expenditure at the same level, household savings also declined”.

Although Ghosh does not dwell on it too much, attention must be paid to the growth of real (inflation-adjusted) income per capita, which is hovering between 5-6 per cent today, as per SBI data. Per capita figures can be misleading as they provide an average — in this case, the average real income growth of everyone in the country, including on the one hand, a multi-billionaire like Mukesh Ambani, and a landless peasant in Jharkhand, on the other. A higher income growth for the former will pull the per capita figure upward, obfuscating the lower income growth of the latter. Hence, in order to get a true picture of real income growth, and improve our understanding of the cause of demand deficiency, it is crucial to disaggregate real income growth by income groups.

The fortunes of the bottom 50 per cent

As the table below makes clear, average annual real income growth per adult for the bottom 90 per cent (between 1980-2015) has been slower than the overall per adult income growth, whereas that of the top 10 per cent is much higher.

Note: The corresponding figure for the middle 40% must read 2.9%, which is missing in the original document due to a typographical error

This disparity in growth rates, translates into, according to Chancel and Piketty, “The bottom 50% of earners experienc[ing] a growth rate of 90% over the period, while the top 10% saw a 435% increase in their incomes.” To put it in simple terms, if an adult belonging to the bottom 50 per cent (A) earned Rs 100 in 1980 and an adult in the top 10 per cent (B) earned Rs 200 in the same year, by 2015, A’s income, in real terms, would be Rs 190 while that of B would be Rs 1,070. The skewed nature of real income growth is apparent in the fact that B’s income went from being twice of A’s in 1980 (B/A=2) to being more than 5 times A’s income in 2015 (B/A=5.6).

One can anticipate an oft-repeated criticism by those who feel that focusing on inequality is misplaced as what really matters is the absolute increase in the incomes of the bottom 50 per cent. After all, in real terms, their incomes have nearly doubled in the last 35 years, putting greater purchasing power in their hands. Leaving aside the social and political consequences of growing inequality, this line of reasoning ignores the inadequacy of inflation-adjusted income data to capture the impact of privatisation of public services in post-liberalisation India.

As the economist Prabhat Patnaik explains:

To see how privatisation makes a difference to the consumer price index, let us take a simple example. Let us imagine that in the initial year, every agricultural labourer went to a government hospital, while in the current year, because government hospitals have been run down in the intervening years, everyone is forced to go a private hospital. If all prices, including government hospital charges remain unchanged between the initial and the current year, then the CPIAL [Consumer Price Index of Agricultural Labourers] would show zero inflation. But because the agricultural labourers are forced to go to private hospitals which have much higher charges, the fact that government hospital charges have remained unchanged makes little difference to them. Indeed if health expenditure accounted for 30 percent of a labourer’s total expenditure in the base year, and if the charges of the private hospital are double those of the government hospital, then in this particular example the actual rate of inflation which the agricultural labourers face is 15 percent and not zero as the CPIAL would suggest. The CPIAL, by not taking into account the effect of the massive privatisation of services, thus seriously underestimates the rate of inflation and hence seriously overestimates the magnitude of the real wage increase.

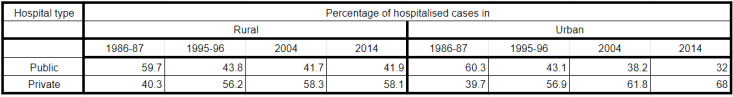

Staying with the example of healthcare, NSSO Survey data shows a huge decline in the share of public hospitals for in-patient treatment since the imposition of neoliberal reforms in 1991.

Private healthcare institutions now provide more than two-thirds of all in-patient healthcare services all over India (rural and urban), with an average cost of treatment more than four times that of the public sector.

To sum up, a greater share of the incomes of the poorest people are diverted towards healthcare and education, which, along with a general squeeze on subsidies and welfare programs, grossly undermines whatever income growth they witness. Moreover, such a squeeze is not reflected in the inflation-adjusted income growth figures, and one can deduce that the actual income growth in the last 35 years is certainly less than 90 per cent, as suggested by Chancel and Piketty’s findings.

Given that the bottom 50 per cent of the country’s working population, comprising nearly 400 million people, have near-stagnating incomes, is it really any surprise that there is weak demand from below?

A systemic crisis in our gilded age

At the top, though, the story is same, yet different. While the fruits of India’s growth have increasingly accrued to the top 10 per cent, demand is anemic in that sector as well, for entirely different reasons. In an interview with the Indian Express, Dr Rathin Roy, member of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council (PMEAC) and director of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, acknowledged that, “Since 1991, there has been a conscious attempt to ensure that the principal engine of growth is the consumption by the top 100-120 million (people).”(emphasis added.)

But consumption trends within this sector of the country have undergone a change, he noted:

But when you all (the top 10 per cent) have bought your cars and houses, what will you consume next? You will want to go for holidays abroad, have your healthcare done in Singapore, you will want your children to study abroad, and that is what is happening now. This additional discretionary demand this 100 million is generating is increasingly moving to things that India doesn’t produce… If you look at the import bills for foreign holidays and education, it is going up by hundreds of percent a year for the last six-seven years. So domestic consumption is plateauing for a structural reason.

Herein lies a central contradiction of neoliberalism, and of capitalism in general — by its natural progression, through which it enriches the few and impoverishes the many, it grows increasingly unstable and unsustainable. If macroeconomic viability was a concern, it would be obvious that the vast amount of wealth capitalism generates should be more equitably distributed; otherwise, there won’t be a lot of people with the money to buy all the commodities it produces. That is how a rational system would function. But capitalism, no matter what you may have heard, is not a rational system — it is institutionalised greed, propped up by violence and misery.

1 thought on “A Sinking Feeling”

Comments are closed.